Modelling the eclipses of KIC 2856960 is a matter of setting up a number of spheres with orbits defined by Kepler's laws (initially ignoring dynamical effects that cause evolution of orbital parameters), and then computing the amount of flux we can see at any given time, accounting for any eclipses. One has to account for limb darkening which causes stars to appear dimmer from the centre to the edge of their visible faces, but otherwise this is not a very difficult exercise. However, the initial results were catastrophically bad. to see why, read on.

We were expecting that the system would be well modelled with just three stars. We were very wrong ...

|

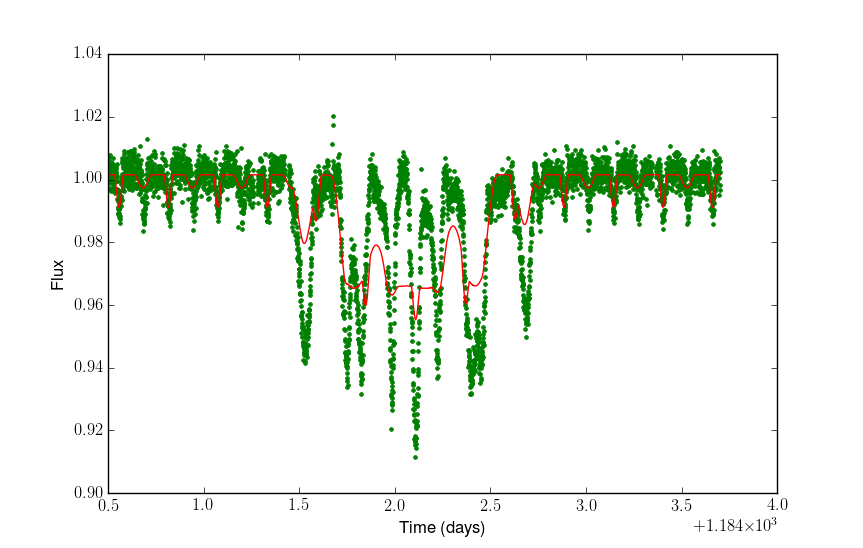

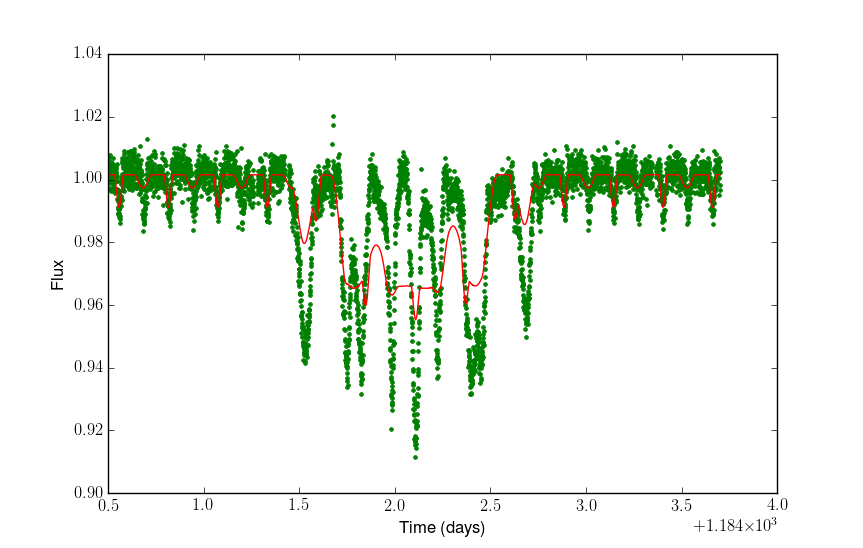

Left: A physically-consistent triple star model fitted to the one tertiary-event observed by Kepler in its short cadence mode. The binary eclipses (2 per 6 hour orbit) are visible away from the tertiary events which occur as the binary passes in front of the K star tertiary object. The data show that one star of the binary can move across the face of the K star to cause a dip, and then move off again. The model is able to replicate this at the start and end of the events, causing the leading and trailing isolated dips, but in the middle it is unable to match what is seen in the data, essentially because the binary orbital separation is too small. |

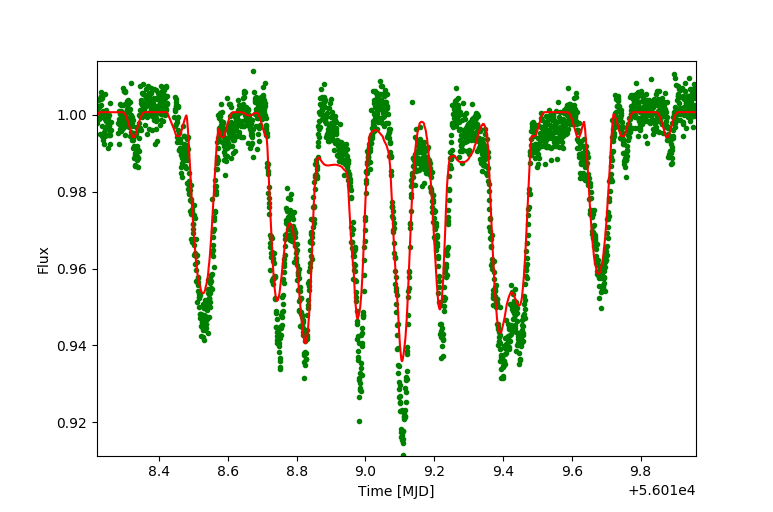

Here is a quadruple model with a star in an "inner triple" with the close binary. It's far from perfect, but an improvment on the pure triple model.

|

Left: A physically-consistent quadruple star model fitted to all the Kepler data, but only shown against the short cadence data here. This model has an unseen extra star in an inner triple with the close binary. In this case the inner triple period is 20 times shorter than the outer 204-day period, but other integer multiples do as well (or as poorly). |

The quadruple model is better, but still not good. It requires an extra star in an orbit that it close to a precise integer divisor of the outer 204 day period. This surely cannot be true for long, hence I would expect the tertiary eclipse events to change with time, and possibly disappear entirely, hence this campaign. I want to see if the events still happen at all, when they happen if they do, and whether thet are significantly different in behaviour.